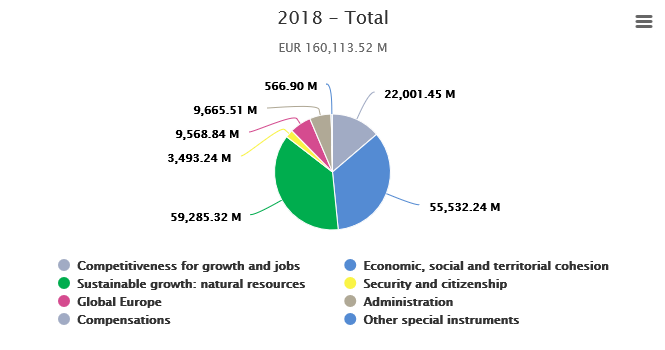

The European project as it is known today is an unprecedented framework for economic, social and political cooperation like Europe has never experienced. Like national governments, the EU also has a budget which is used to achieve policy implementation, such as achieving food security, widening opportunities for education and training, economic regeneration of towns and regions, supporting technological innovation and making a difference for economic inclusion and social cohesion.

This has an impact via hundreds of thousands of beneficiaries, which includes farmers, universities/research centres, workers and small- and medium-sized enterprises (SME). This accounts for about 2% of the combined national budgets from all EU countries. This small portion of the combined national budgets translates to more than 80% of the overall budget of the EU to fulfil these objectives. Contrary to popular mythology, control of how this money is spent is carried out by two bodies, which are the Commission and the European Court of Auditors after the end of the financial year. As this money stems from the taxpayer, it is right and proper that public money is spent for the correct purposes and there is accountability and transparency.

As the current period of the multi-annual financial framework (2014-2020) is set to expire and the 2021-2027 budget is currently under deliberation, it is time to discuss how the budget can be utilised in a pragmatic and constructive fashion to address the economic development, investment and tackling climate change.

Current outline on spending on capital investments, sustainability and economic growth

One of the largest units of this spending, which has European parliamentary approval and provisional approval from European ministers, is InvestEU, whose objective is to act as a launchpad for investments that replaces the European Fund for Strategic Investments (EFSI). The end goal of InvestEU is to generate almost €700 billion to support projects that specifically have objectives supporting employment, investment in renewable energy technologies to achieve the objectives of the Paris Agreement, fostering economic, territorial and social cohesion over the lifetime of this multi-annual financial framework.

Building on this, the InvestEU Advisory hub will integrate 13 different services to provide a single point of contact. The Youth Employment Initiative, established for the financial period of 2014-2020, is also set to be incorporated into the 2021-2027 EU budget as part of the European Social Fund Plus (ESF+) to tackle youth unemployment, equipping people with the skills to adapt to changing employment trends and labour markets.

The Connecting Europe Facility (CEF) is another EU funding instrument that targets infrastructure investment at a European level, spending €28.7 billion since 2014 on projects related to transport, energy and the digital single market. This supports trans-European networks for transport, energy and digital services sectors, ensuring investment in public transport networks, providing broadband and telecommunication facilities and ensuring all have access to affordable, secure and sustainable sources of energy.

Horizon 2020: A vehicle for the creation of new industries

In the area of scientific research and innovation, Europe is a world leader in collaboration for research and development. These researchers are highly mobile and multinational professionals in fields such as chemistry, biology, physics, and engineering. We are so successful in this field because of the people and talent we have in our possession, our world-leading universities/research institutes and freedom of movement, allowing talent to have no barriers of entry to moving across member states to work on a project – an intellectual single market.

Diversity is a strength in our field as many individuals have different specialisations, different scientific backgrounds and different ideas around how to tackle specific scientific challenges. This appreciation of diversity attracts the talent of those who are from European countries, and those who are from Africa, Asia and the Americas. This kind of creative thinking, openness to new ideas and investment in research and development was also attributed by many as the main contributor to the rise of the United States as an economic, political and military superpower during the 20th century.

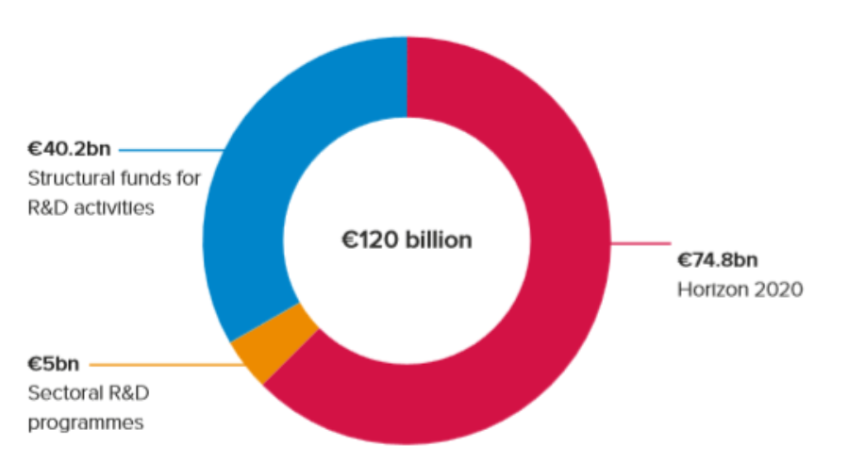

In the EU, these scientific endeavours are primarily funded by Framework Programmes (FPs), which is the main EU funding mechanisms for research. A Framework Programme funds cutting-edge research, with the previous FP7 framework programme (2007-2013) producing more than 170,000 individual publications, 47% of which published in high-impact peer-reviewed journals, 54% of all peer-reviewed publications being open access, with projects generating more than 1,500 patent applications as a result.

The economic impact was assessed in the ‘ex‐post‐evaluation of the 7th EU Framework Programme (2007‐2013)’. The macroeconomic effects of the FP7 programme have forecast that ‘the FP7 framework is on target of triggering economic growth of approximately €20 billion per year over 25 years, or €500 billion in total, through direct and indirect economic effects. It was also estimated that the economic impact also translated into direct job creation, based on staff cost for researchers ‘directly created 130,000 jobs’ and indirect jobs created via new technologies ‘approximately 160,000 additional jobs are indirectly caused by FP7 over a period of 25 years’.

The current framework, for years 2014 - 2020, is called Horizon 2020. It will provide €74.8 billion to implement this initiative of making European research and innovation globally competitive. At the heart of this research lies a desire for both the public and private sector to combine their efforts to take an idea from the laboratory all the way to the market to provide sustainable growth and jobs, boosting the living standards, health and prosperity of millions of ordinary citizens. Between the years 2014 and 2016, nearly 14,000 grant agreements were signed, with grants amounting to €24.8 billion, with more than 20% of the funding going towards SMEs.

As of May 2019, 277 SME from 25 countries will receive an additional €13.7 million between them to assist in getting projects to market. These projects range from the world’s first foldable car seat to a satellite monitoring system for wildfires, a rapid screening for breast cancer, smart chargers for mobile devices, 4D asset modelling for drones, artificial intelligence and many more projects.

Looking ahead: The 2021-2027 Multiannual Financial Framework and beyond

Funding for technological and infrastructural development has been demonstrated to increase the global competitiveness and productivity of our economies, assisting investment across Europe and providing sustainable economic growth in the long term. This will also help mitigate challenges brought about by globalisation, such as automation for example. These measures will ultimately lead to skilled, stable and well-paid employment for the future while mitigating the social and environmental challenges brought about by climate change and rising income and wealth inequality in our own countries and across Europe.

Although the Commission largely has the right approach, this political will needs to persist in the long term before the real material benefits of these actions can be felt in communities that are crying out for new industries to set up in their area, which often had their old industries such as steel production or coal mining disappear, with nothing to replace the jobs that were lost.

Therefore, increasing the budget for this kind of technological development and investment is arguably a sensible way of spending public money. Although there have been positive endorsements for modest increases, we will have to wait and see what the substance of the final proposals are. One area that is lacking in this current approach is teaching and mentoring in entrepreneurship. For this approach of combining innovation and entrepreneurship to work, this must be matched by the knowledge of how to start a business, how to handle finance and taxation, how to raise investment and obtain grants, and how to market your products for both domestic and international clients.

For this purpose, there should be a substantial effort to change the mindset of those who are just about to enter the labour market and those already in work. Collectively, we should move away from a single-minded search for employment, but seek to take control and create our own opportunities via the creation of small businesses. Therefore, a program to implement these objectives should be created via increasing the budget by €2 billion across the Multiannual Financial Framework, specifically for training and seminars on this topic across the EU member states for those that are working in scientific/engineering research, and computer science.

The aim would be to directly reach 500,000 people and give them guidance and support on setting up and managing start-ups, across the lifetime of the budget. These workshops can be conducted over a short period of time at higher education centres, or as a part of a summer schools programme, to give people from technical and non-business backgrounds the basic skills and understanding of how to register and structure a business, how to write a comprehensive business plan, how to apply for loans, grants and investment from private investors, how to network, how to brand and market a business to potential clients and so on.

This kind of programme can become a “mini-MBA” for scientists and engineers, giving them a perspective of how to translate their scientific projects into business opportunities.

Pursuing policies that will see a reduction in spending on a European level may be seen as a badge of honour for many Eurosceptics. However, such an ideological and dogmatic approach may not be sensible because reducing spending on capital expenditure such as on infrastructure or development of new and disruptive technologies can do long-term damage to economic growth. It is important to be more ambitious in our support of research and development activities as China is allocating significant resources to their industries.

If the political will disappears, we could lose out to Chinese industries and see our economies stagnate and jobs disappear. The single most important point that democratic governments must take on board is that we are living through a period of profound change, brought about by a technological revolution that may well have further-reaching consequences than the industrial revolution in the 19th century.

When the full impact of automation, artificial intelligence and computing is felt, governments, economies and people will need to be able to adapt to change. This will enable society to take advantage of these changes by applying, for example, disruptive technologies in our healthcare systems that will aid early, low-cost diagnosis of diseases, potentially saving our healthcare systems billions over the coming decades. By making collaborative, multilateral efforts in this direction, governments can deliver for future generations of citizens by rising to the challenges brought by globalisation, and be the change that people want, rather than the defenders of the status quo.

Whatever people may think, these challenges are not something that unilateral action alone can solve. We need to be prepared for change, to imagine new possibilities for the future, and tear down barriers. We should also never take anything for granted, as nothing has to stay as it is.

Follow the comments: |

|