They are the sons and daughters of Chinese immigrants who arrived in this sunny European country during the 1980s and 1990s. Some of them feel like ordinary Spanish citizens; after all they were born and raised in Spain. However, the majority of them do not share this feeling – because as they were growing up, other kids liked to yell “Chinese!” at them because of their Asian features.

Chinese immigration to Spain: a brief history

The history of Chinese migration to Spain is not comparable with that to Southeast Asia, the US and South American countries like Peru, where the first Chinese people arrived as early as the end of the 19th century, most of them as indentured labourers. While the first Chinese people from Qingtian arrived in Spain during the First World War, the numerically larger wave of Chinese migration did not begin until the 1970s – the decade in which Spain established diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic of China.

Most of the young Chinese who were motivated to earn money and improve their quality of life in a European country came from the rural areas of the Zhejiang Province, which has a long tradition of emigration. The trend boomed in the 1980s, resulting in a mostly uneducated populace moving to countries like France and Italy in large numbers.

The main reason Chinese people chose a particular European country was usually because they already had relatives there. This was the case for the parents of Charlie Ye, a young Catalan whose family emigrated from Qingtian to Spain with the help of relatives living there; likewise for Carol Zhou, 24, one of the daughters of a Qingtian family who settled in Barcelona. Her mother arrived in 1986 at the age of 16, her father followed a year later. Part of her mother’s family was already living in Holland, but her grandfather moved to Spain due to problems with obtaining legal residence status. Carol Zhou’s mother travelled with her then 13-year-old brother to Guangzhou to obtain a Spanish visa and then by plane from Hong Kong to Madrid.

"My mother told me how hard the journey was. And then they were in a strange new country.” Most newcomers, mostly young men, would not let this bother them. They simply didn’t know in which country they would end up and for those who didn’t even know what Europe looked like, it made no difference whether they ended up in Britain, France or Italy anyway.

Nonetheless, Spain was not a dream destination before the 1990s. After Franco’s long dictatorship, the conditions were everything but ideal. But eventually, the Chinese population increased strongly in the 1990s. About 5,000 people from the People’s Republic of China lived in Spain at the beginning of the decade. Within 10 years, this figure had increased to 30,000 – without counting the illegal immigrants. One of the most popular methods of crossing the border into the Spanish kingdom was paying money to one of the shetou who smuggled Chinese citizens into Spain with fake Japanese passports. These so-called “snakeheads” are Chinese gangs specialised in smuggling people into other countries. However, illegal immigrants were later able to obtain legal residence status thanks to an immigration amnesty by the Spanish government.

The sons and daughters of the diaspora: between prejudice and a better life

Today, there are more than 200,000 Chinese people living in Spain. This number does not include those who have already acquired Spanish citizenship. According to the Spanish census bureau, almost 70% of them come from the Zhejiang province. In this respect, China could be rather seen like a continent than a country, as we are more talking about immigration from Qingtian or Zhejian and not China as such.

After a decade of steady growth among the Chinese population, many of whom opened restaurants throughout the country, Spanish citizens became concerned. Some of them began to make jokes about the “yellow peril”. Writer and translator Berna Wang reported that after many years without any problems in Spain, for the first time in the 1990s she was starting to be victim of verbal abuse and insults from taxi drivers enraged by her Asian appearance.

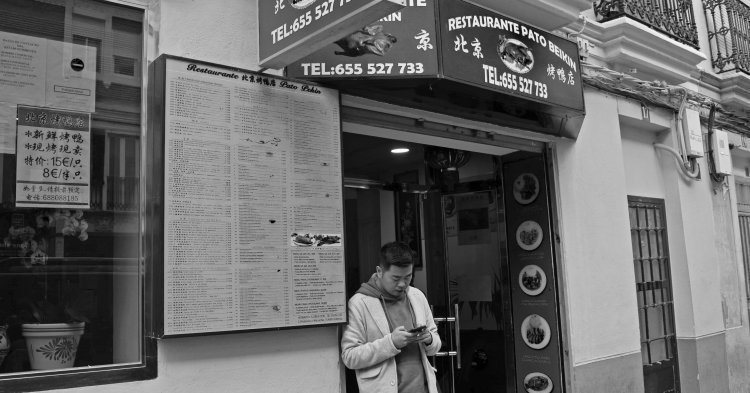

In the 1990s and 2000s, Spain enjoyed good economic conditions. The tourism industry grew rapidly and with immigration from all over the world, Spain became a highly developed country. And today, the Chinese community itself is very diversified, spanning from owners of affordable restaurants and shops over entrepreneurs who open travel agencies, hairdressing salons and driving schools to service other Chinese expats, to a variety of other professions. Spain has even seen the development of “Chinatowns” in the larger cities like Madrid, Barcelona and Valencia, for example.

Carol Zhou recounts how her parents first worked in another Chinese restaurant until they had saved enough to open their own. However, this was neither their first nor their last enterprise, as they were always trying to save to get new and innovative business models up and running in other places. “The pursuit of a better life never ends. They were able to achieve smaller goals and then began to strive for larger ones. Ever since I was a young child, I’ve seen my parents try new things, always with the goal of improving their present situation,” she recalls.

The sons and daughters of Chinese immigrants have grown up being the only ones with Asian facial features in their classrooms and workplaces. Every day they have been and still are asked by their fellow Spaniards where they come from and why their Spanish is so good. On the other hand – considering that their parents often spoke regional dialects – they see themselves confronted with questions from Chinese visitors about their poor level of Mandarin.

Follow the comments: |

|