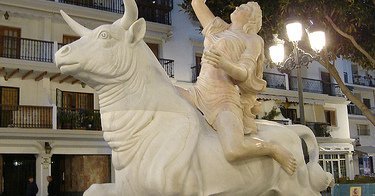

European political mythology

Far from being a purely decorative motif, Europa on the bull is a politically freighted symbol. It serves a good example of how a classical myth can operate as a powerful ideological tool. It also shows how people of the modern world are not just analyzers of ancient myths. In some respects we, no less than 2000 years ago, actively use and exploit classical myth. We will have an in-depth look at a good example of how European politicians like to rely on the myth to get their message across:

“You could of course be forgiven for the myth analogy, after all, our very name is rooted in mythology – Europa being a beautiful maiden carried off by the God Zeus in the guise of a bull. But today’s Europe, beautiful though she may be, is no longer that kind of girl.”

This quote comes from a speech made by former EU’s External Affairs Commissioner, Ms. Ferrero-Waldner in 2007. As Ian Manners already pointed out in a recent article in the ‘Journal of Common Market Studies’, Ferrero-Waldner deploys the bull myth as a means of conveying the foreign policy change that the EU has undergone since its creation. According to Ian Manners, there are three ways to read the myth, each coinciding with a phase in contemporary European foreign policy:

– In the first version of the myth, ‘the rape of Europa’, the bull represents the extreme forces of nationalism, violence and oppression embodied in Nazism. In this version Europa is portrayed as a victim of brutal force to which it reacts in vain. This interpretation provides the foundations of a united Europe: it shows how European integration helped overcome evil forces and how these experiences are inherently present in the European wounded ‘soul’.

– The second interpretation of the myth is created after W.W.II. From then on, the myth can be read as the ‘seduction of Europa’. The bull is here represented as the liberator of Europe, the United States of America, that eventually marries Europa. In this sense, the American bull helps Europa escape its devastating past and escorts her towards a brighter future, albeit one involving closer relationships across the Atlantic ocean. A recurring theme in many speeches nowadays using the metaphor is that we are still in this interpretation of the myth while we should move on more independently. Europa installed herself so safely on the back of the mighty, American beast that our girl – contrary to what Ferrero-Waldner in the quote above suggests - does not wish to give up her comfort and try to swim with own force in turbulent waters. The consequence is that the world – including Europe – still only looks at the USA to solve big global issues.

– The last myth of the ‘transition of Europa’ is a less obvious metaphor and goes beyond rape and seduction to portray Europa’s journey as a metaphorical passage. In this interpretation, Europa is killed by the bull during the 1930s and 1940s. However, after the war a post-national Europa is reborn, stronger than ever. The fragile maiden had become a self-conscious and responsible mother and queen. This version can also be seen as a merger of the first two foundational stories: Europa is both a traumatized product of aggressive politics as a enthusiastic promoter of peaceful policies and a powerful player in the international arena. It is within this interpretation that the quote from Ferrero-Waldner can be situated.

These examples of interpretation expose the great adaptability of the myth, but still the rape of Europa is read selectively in these modern interpretations and always has a positive outcome. The reason might be that all these version were created by pro-Europeans.

However, we should stress that using a myth as a symbol is a complex game that always involves selecting some parts of a narrative and suppressing others. Consequently, the process of communicating a myth cannot be controlled because it contains so many layers of possible meanings. Concerning the bull myth, a less positive portrayal of European politics is not hard to think of. And thus it is no surprise that at the other end of the spectrum, the story has also been used favorably by the anti-European movement, who finds it shocking that the European Union so openly adores such a violent tale. Nevertheless, these Eurosceptics and Europhobians retell it themselves to illustrate their fear for more European integration. For them, the myth – as a semi-official EU symbol – portrays the European undemocratic elite as the bull that lies about its identity and its intentions and ends up raping Europa, being the European people that have no say in their faith.

For an example: watch the video where eurosceptic MEP Nigal Farage uses the myth several times as a metaphor to attack his political opponents.

A father figure for Europe?

At the end of this article, we bring an alternative – and maybe less controversial - founding myth for Europe to your attention: Greek mythology also tells the story of Europa’s brother, Cadmos. He was ordered by his father to bring his favorite child Europa back. Cadmus went to Delphi to seek help from the oracle in finding his sister. The oracle told him to instead seek a new home. Cadmus was told to take a cow as a guide, follow it until the animal dropped dead of exhaustion and establish a city on the exact spot where it had died. And that is how, according to the myth, Cadmos ends up founding the great city of Thebe and has many famous descendents.

We can interpret this myth as follows: while he is searching for Europa he becomes the ancestor of the continent and community that would be baptized with his sisters’ name. In the end, he never manages to complete his task and find his sister. Which points to the fact that the process of building Europe can never be assumed to be completed… The story of Cadmus is not popular because it is not as ‘sexy’ and its symbolic relevance rather far-fetched.

Multi-interpretable but not multicultural

To conclude, a small critical note. It should be clear by now that mythology has some relevance for the construction of European symbolism. Yet, before happily spreading Europe’s narratives, we should keep some skepticism vis-à-vis the mythical underpinning of European society. These legends – however interpreted - narrow the European inheritance down to Greek civilization. Without minimizing the importance of our venerable Greek cultural roots, we do believe Europe ideally deserved a more multicultural myth as founding story given the fact that it is one of the most culturally diverse areas of the world.

This being said, we hope this article has passed you some ideas and inspiration to create your own interpretation of Europe’s fascinating myths!

Follow the comments: |

|