Le Taurillon: Andreï Vaitovich, many thanks for agreeing to this interview! For six months, Belarusians have been demonstrating against Lukashenko and his fraudulent re-election in August. What are the peoples’ current frame of mind? Are they still hopeful?

Andreï Vaitovich: You could say that the day after the election, the Belarusians woke up in a new country. For three days, we didn’t really know what was happening: internet connections were cut, mobile networks barely worked. It was only after a few days that we began to realise the gravity of the situation. Thousands of people had been arrested, mistreated, tortured or even killed by the police. The protests did not end on the night of the election, as Lukashenko had wanted.

The regime feared for its survival, but the line had been crossed with the first deaths. The people have not forgotten, and they are not ready to forgive. Since then, the unprecedented mobilisation has shown that the dictator no longer has real popular support. Only the inner circle and the security forces are still loyal to Lukashenko despite everything.

The never-before-seen repression has undoubtedly scared some. No-one wants to end up in prison. Nonetheless, people are still determined and even if the type of action changes, the anger is not disappearing. On the other hand, Belarusians feel a bit drained. It’s winter and conditions are difficult for mass demonstrations, and the second wave of COVID-19 is another constraint. For the first time, without a doubt, Belarus is impatiently waiting for the return of mass demonstrations in the spring, or perhaps another kind of action that we’re not aware of yet– the population is very resourceful. The saying “hope dies last” corresponds well with the current state of affairs.

Image text: “The day after the election, Belarusians woke up in a new country.”

LT: In what way is the current uprising different from other revolts of the past, like the ones led by the pro-Western Zubr civil rights movement in the 2000s?

AV: First of all, the difference is related to the changes that Belarus went through during the electoral campaign. On the one hand, the deplorable economic, health and social situation mobilised those who were known as “apolitical” until then. On the other hand, the appearance of new faces has motivated the majority, and even those who perhaps voted for Lukashenko in the past saw hope of a resurgence.

In 2010, 2006 and before, the revolts did not last because they mainly brought together the political elites of the opposition, the middle class and the intelligentsia, the elite based in Minsk. In 2020, it was provincial towns that were in the frontline of the movement. The big cities and the capital had no other choice than to follow them. Another difference is the degree of repression, but also the reaction of the international community and the increasingly important Belarusian diaspora movement abroad.

LT: The repression imposed by Lukashenko in response to the demonstrations has been very hard. Do you have information about the situation of the numerous political prisoners in the country?

AV: In six months, more than 35,000 people have been arrested arbitrarily. According to human rights defenders on the ground, five people have died during demonstrations; according to the opposition, the number is ten. On 13th February [Editor’s note: The interview was conducted on 13 February], there were 246 people on the list of political prisoners, and this list continues to grow every day. We know at least 1,000 proven cases of torture. There is already around a hundred people who have been sent to prison because of political reasons. The consequence is that the rate of emigration has exploded. Between 30,000 and 50,000 Belarusians have been forced to leave their country.

Image text: “Between 30,000 and 50,000 Belarusians have been forced to leave their country.“

LT: The de facto leader of the Belarusian opposition, Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, is exiled in Lithuania. What is her influence on the course of events? Does she have any specific way to act?

AV: Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya has become the face of the movement, now recognised by heads of state in Europe and around the world. She is also the voice of hundreds of thousands of Belarusians who have been demonstrating against Lukashenko’s re-election for months. Every week, she meets international political leaders and brings attention to the most recent developments in the crisis. She now has hundreds of people around her, who have different backgrounds: former diplomats, former police officers, volunteers and academics. They all are in constant contact with Belarusians on the ground, neighbourhood-level activists and strikers.

It is not really Tsikhanouskaya who leads the demonstrations in Belarus, and the demonstrators are not following directions from her team, from Telegram channels or from anyone for that matter. Tsikhanouskaya’s main influence is to remind the international community that even if the solution to this crisis is inside Belarus, Europe and the rest of the world shouldn’t forget this country. And if the goal is achieved, a free and transparent election will be organised on the watch of election observers from the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE).

LT: Despite the sanctions targeting high-level dignitaries in the Belarusian regime, the EU’s reaction seems very weak. What should the 27 EU countries, and France in particular, do to support Belarusians?

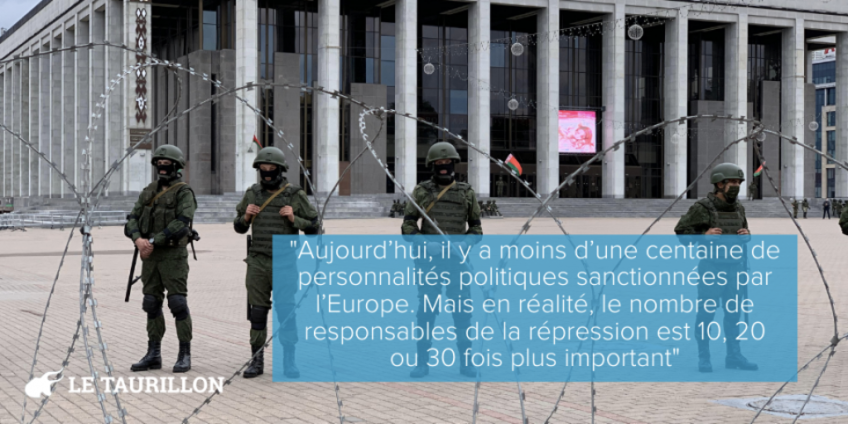

AV: Europe’s reaction was firm and immediate, but the longer the crisis lasted, the more it seemed like too little, too late. Since 9th August, the EU has already adopted three sanction packages. The fourth list should be revealed by the end of February, but we know that there are lobbyists inside the EU institutions who try to protect the regime’s interests. At present, less than a hundred political figures are under European sanctions. But in reality, the number of people responsible for the repression is 10, 20 or 30 times larger. This includes people who have positions within the regime, judges who orchestrate political trials, so-called journalists who shamelessly feed the state’s propaganda machine, and special forces who execute illegal orders.

We can see that achieving unanimity is difficult for Europe. Some EU member states are doing a lot more than others. Lithuania and Poland have been exemplary since the start of the crisis: they have organised humanitarian corridors by welcoming victims of repression, but also students who have been expelled. The Czech Republic has received and treated torture victims. We have examples of solidarity here and there, but it’s impossible to observe collective European solidarity by the 27 member states.

Europe needs to be more firm, reactive and concrete, especially the older European democracies like France. French diplomats from time to time talk about their commitment and support for Belarusian civil society, but in reality, their words are not often backed up by deeds. The French Ministry of Europe and Foreign Affairs sent a new ambassador to Minsk, who presented himself to a Belarusian regime that France no longer considers legitimate. For many weeks, the Embassy has been working with a skeleton staff, which has kept to the classic framework of diplomacy: meetings with officials from the regime, but also with the opposition and human rights defenders. What for? The last 26 years were apparently not enough to understand that this regime will never give up, and that it will never accept democratic values.

Quick actions are needed because this is a matter of urgency. We need to go beyond our bureaucracy and start acting. If Belarus’s neighbours can do it, I doubt that France does not have the capacity to offer real rather than just symbolic help. We must be consistent: since we have met the exiled opposition leader and demanded Lukashenko’s departure, we should propose solutions and follow through.

Image text: “At present, less than a hundred political figures are under European sanctions. But in reality, the number of people responsible for the repression is 10, 20 or 30 times larger.”

LT: Since the start of the uprising in August, you have regularly reported on the situation on the ground, especially via Twitter. Can you tell us more about what is involved in being a journalist in Belarus?

AV: Journalism has become a crime in Belarus. In six months, more than 400 journalists have been arrested simply for doing their job. Eleven journalists are currently in prison and risk long sentences. Foreign media have been denied their media passes, with some rare exceptions. The situation is dramatic, and according to Reporters Without Borders, Belarus is the most dangerous place in Europe to be a journalist.

Support for independent journalists on the ground is essential, and must be reinforced by the international community. Every day, my Belarusian colleagues and their loved ones are threatened and may be imprisoned. At the same time, Europe does not mind the regime’s so-called official “journalists” working freely in European countries and manipulating information about sensitive subjects like the COVID-19 pandemic. We really need to ask ourselves if these state “journalists” have the right to media passes in our European institutions.

LT: Are we witnessing an emergence of citizen journalism in Belarus? How do citizens cover the events happening in their country?

AV: In a country where the traditional media – TV, radio and print press – are 100% controlled by the state, and where the demand for independent and transparent information is high, this has already been happening for many years. Recent surveys by Chatham House show that only 16% of Belarusians trust official media, whereas the figure is 50% for independent media. This is online media, of course, and that’s why the regime shut down the internet in the first days after the election.

During the demonstrations, us journalists heard slogans like “Thanks to the press” all the time, and that was our source of energy. But now that repression against journalists has been ramped up and journalist teams’ presence has decreased at an incredible speed, people on the streets have been and continue to be witnesses and sources for us. For example, when the format changed and the gatherings have been held in residential neighbourhoods, it was no longer possible to send in a team or even an individual journalist. That’s how we work today: to cover a maximum of events, whilst exposing ourselves as little as possible. This emergence [of citizen journalism] is not only technological or due to social media, it’s above all because of the desire for change: people’s desire to live in a free country, and for journalists to be able to do their work properly.

Image text: “Even if the solution to this crisis is inside Belarus, Europe and the rest of the world shouldn’t forget this country.”

Follow the comments: |

|