The far and the near right-wing

In an interview for the Austrian Kleine Zeitung this month, Hungarian PM Viktor Orbán said that the European Parliament should follow the “Austrian model”, meaning the cooperation between the far-right Freedom Party (FPÖ) and the center-right Austrian People’s Party (ÖVP). In Orbán’s view, the EPP should, in the same fashion, cooperate with Le Pen, Salvini and the rest in order to ensure a workable majority in the Parliament. In the same interview, the Hungarian strongman abandoned Manfred Weber’s campaign for President of the European Commission, a camp where he uneasily remained after being suspended from the centre-right political family earlier in the year.

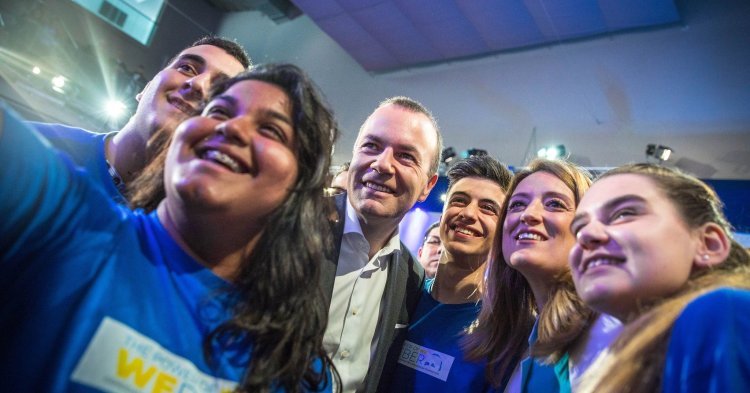

Weber’s increased criticism for Orbán – who leads one of the parties in the EPP with the highest degree of support – has served as the perfect example of the way in which the centre-right has tried to distance itself from the far-right across the continent. Ranked with the best chances of getting the top job at the Commission, Weber has stressed unity during the campaign, but also topics such as the decrease of bureaucracy, job-creation, digitalisation, home loans financed by the European Investment Bank, a European FBI and a stronger Europol. Addressing younger voters, he also vowed to fight for the global ban of single-use plastics.

European models

The centre is getting closer together in Europe in an effort to block the far-right from power, but the situation differs from country to country. In Austria, the “model” is working through the Kurz government and its fixation on security – but even there, the far-right has been ‘domesticated’. In Hungary, the opposition to the deeply conservative Fidesz is the ultra-right and xenophobic Jobbik party.

In Poland, the European Coalition (KE), made out of pro-European centrist parties, including the centre-right Civic Platform, the Greens, the Polish People’s Party, the Feminist Initiative and the Social Democracy of Poland party, has been set up to counter the conservative and Eurosceptic Law and Justice Party (PiS).

In Spain, the centre-right Popular Party (PP), desperate to win back support, tried a different strategy – that of appealing to the voters of the far-right Vox party. The successor of Mariano Rajoy, Pablo Casado, led the party right-wards and replaced all of the top people in PP, reviving topics such as abortion, a turn that virtually no one supported. As a consequence, PP obtained its worst electoral results in memory, while the centre-right liberal Ciudadanos upped its numbers.

In Sweden, a post-electoral deadlock was broken only when the centre-right Centre Party came together with the Social Democrats and the Greens in order to keep out the far-right Sweden Democrats and the far-left Left Party. In doing so, the three parties tempered each other – the senior partner in the coalition, the centre-left Social Democrats, abandoned an increase in income taxes and the limiting of profits of private firms operating in the welfare sector, and increased environmental taxes.

In Estonia as well, the centre-right Reform Party, which supports lowering taxes and the minimal state, won the last elections. Together with the Centre Party of PM Jüri Ratas, it was in talks to keep out the Conservative People’s Party (EKRE) despite its almost 18% of votes. Later on, the left-leaning Centre Party, breaking their past promises, made EKRE its junior coalition partner.

The predominant European strategy for the centre-right has not been that of Austria, namely a coalition between the centre and the far-right – on the contrary, it has been one which focuses on the centrist forces as a stop to extremist groups.

The makers of Europe – A history

The European People’s Party has been at the heart of the European Union since the beginning. Formerly the Christian Democrat Group, the party was formed in 1953 and reshaped in 1976 – but had its origins traced back to the 1920s, to the conferences of Christian Democrats – as a union of conservative parties in the Common Assembly of the European Coal and Steel Community. Robert Schuman, one of the leading figures of the European Union in its early days, also was at the founding of the centre-right group. Built on subsidiarity and integration, the EPP was also one of foremost proponents of a federal Europe.

Despite their strong – rhetorical – tradition of internationalism, it was not the European socialists who built the Community or the subsequent Union. Focused on decolonisation and class issues, the post-war socialist parties of the continent remained national parties, and lingered in the long shadows cast by their counterparts from behind the Iron Curtain. A federal Europe could not have been formed by socialists, whose ideological cousins starved and tortured half of the continent.

However, the centre-left had an indisputable role in orienting several states toward Europe – Labour in the 1950s managed to orient Britain towards Europe, despite their disagreements with the conservative forces dominating the continent at the time. The socialist government of France served a similar purpose in the mid-1950s. It was the European socialists who pushed the idea of a common European security through the European Defense Community (EDC), which aimed to leave West Germany without an army of its own. However, their efforts were proved redundant when Germany joined NATO.

Federalism and the establishment

Privileged, and not disadvantaged, by its ideological proximity to the rising nationalist populists, the centre-right is the only force which can win back voters from the clutches of xenophobia, regressive conservatism and economic protectionism. Instead, it can set European society, as it did before, onto a path of compromise, market economy, globalisation, individual rights and freedoms, social solidarity and federalist integration. The left, for all its merits, can only engage in a race to the bottom with the far-right, a game in which one side promises social benefits, redistribution and protections while the other dangerously raises the bet once more, promising more benefits, a fairer redistribution and wide-reaching protections. The result, in such a situation, is necessarily more division, more conflict and a lack of solutions.

The federalist movement, of course, is transpartisan. It focuses on policies, not political figures, and on the future of the continent, not the day-to-day logrolling. But it has to recognise its allies as well as its opponents. Nigel Farage and his projected 34% of British votes will never agree to a European army, transnational lists, a common asylum policy, a stronger freedom of movement, a common European foreign policy and other policies dear to federalists. But Manfred Weber might. So would Guy Verhofstadt. Frans Timmermans. Ska Keller. Emmanuel Macron. Angela Merkel and even Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer.

The centre-right has led the European Union to what it is today, being in power nearly without interruption since its founding. As such, the EPP can rightly be considered the EU establishment, even more so than the S&D group. In turn, young federalists have looked upon the centre-right as insufficient, obsolete in terms of environmentalism, heartless in social issues and encroached in its market austerity policies. For this reason, the EPP in particular has been considered as more of an opponent than an ally. As for integration, the EPP likes to walk, when federalists prefer running – but to run a marathon you need to first build endurance.

But federalism is not the anti-establishment movement of the disenfranchised and disappointed youth. It is the primary channel through which the European leaders of the future will arrive. As such, it cannot lock itself into an echo chamber of environmentalism, social justice and redistribution, gender issues, uppity left-wing critiques of capitalism or condemnations of the establishment. Instead, it must recognise its potential allies and partners in power and in opposition, engage them, support them, and remind them of their role – because in the end, we will be them.

Follow the comments: |

|