The Conference itself:

To start it would be worth noting that the conference was the pinnacle to conclude the first year of a great programme of events organised by the new Cambridge Polish Studies initiative, in conjunction with Cambridge Ukrainian studies, both of which fall under the Department of Slavonic Studies. You can in fact watch the full conference online HERE if you are so inclined, and there’s a programme HERE which could help you skip to the bits that may interest you most.

‘Cain & Abel no longer’

The first, obvious, point to note when charting Polish-Ukrainian relations is that they are transformed. Professor Frank Sysyn made the argument that where the two had disliked and distrusted one another previously, they were ‘Cain & Abel no longer’. The conference touched on several reasons why this change may have occurred, some positive and some less so. On the negative and more cynical side of things, there is the white elephant in the room of Russia; that oversized geopolitical foe which puts fear into the hearts of Pole and Ukrainian alike. On the theme of elephants, a repeat appearance in the conference was mention of how they are sharing a bed with an elephant, in so far as it wouldn’t matter how nice the elephant was, you still don’t get any of the sheets! In the case of Russia, the two lie next to an elephant which is proving quite willing to stomp on them.

More positive are genuine efforts to improve ties between the two countries. On the Polish side, it is well worth noting that they were the first country to recognise newly independent Ukraine as the Soviet Union broke apart. On the opposite side, Ukrainian media is hugely positive in its coverage of Poland and after the ‘Revolution of Dignity’, Poland’s success story is being looked to as a template for Ukraine to adopt. And on the subject of the Euromaidan in Ukraine, it was interesting to hear parallels being drawn not only between Euromaidan and the Orange Revolution of 2005 but also to Poland’s famous Solidarity movement.

History & Memory:

An unfortunate fallout, and obstacle, to warmer Polish-Ukrainian relations is the persistence of narratives of victims and oppressors. Poland has long wanted to be seen as the ultimate victim: the country having been variously pulled about by merciless neighbours over two centuries and serving as a guinea pig for some of the worst Nazi atrocities. Poland certainly doesn’t have the monopoly on victimhood however. The recent opening of the POLIN Museum in Warsaw will help shed light on the Jewish history of Poland, another group with a strong claim to victimhood. Ukraine too can claim to be a victim having been a repressed national grouping for a good portion of its modern history. It is no surprise then that events such as the Volhynia Massacre got mentioned during the conference. However, the priority of our time was not to rake up these pained memories but rather to suggest and discuss better memories and experiences on which Poles and Ukrainians can build closer relations.

Professor Robert Frost was perhaps my favourite speaker there, and he made the point most emphatically of all that the lands of what was once the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth are far more a land of peace than a land of war. He cited as an example the border between Prussia and Poland, which remained static from the 15th century through to the First World War. The early modern era was raked over quite substantially for a conference on 21st century relations, simply because it is in the times of the Commonwealth that one can find people of all different ethnicities getting along. It would be far more preferable, and even glorious to the peoples of Eastern Europe, to emphasise the history of times before the shameful and short twentieth century. The same case was made for Literature. Many of the cultural heroes of this region held ethnicities living in the ‘wrong’ land, and the successor countries to the Commonwealth need to learn to once more share their heroes! Professor Frost also made a strong case for looking at local history. Where the history of nations has divided and destroyed, local patriotism is, at worst, merely a cause of blocked roads as tourists flock to see re-enactments of medieval battles.

On the subject of history and memory, the issue of teaching the past came up. School curricula, whether in Poland and Ukraine, or in Japan and China, are still far too nationalistic. I learned at this conference that it is common to compare Poland and Ukraine to France and Germany, a comparison tinged with hope that their relationship can become as radically better as the one that developed following the Elysée Treaty. In that vein, it would be a worthwhile exercise for the two countries to formulate their own equivalent of Histoire/Geschichte, the bilingual history textbooks that have had the aim to bridge the two countries.

Comparison with west European integration:

It’s a common way to make an argument, to use comparisons, and this conference was full of them. Poland and Ukraine were compared with one another; these two protagonists were compared with the Franco-German axis; and parallels were drawn between the increasing warmth of relations in Eastern Europe and the integration that took place in Western Europe. The case was put that to an extent a common fear of Russia has been important in bringing the two countries closer together. Ukraine needs friends in a world where Russia cuts gas supplies with impunity, or slices off chunks of territory with a similar disregard for international law. Poland is more qualified than most countries to know the problems that come from being next to Russia. Furthermore, it is clearly in Poland’s interests to have a strong Ukraine integrated into the European project. The stronger and more prosperous the territory is between Warsaw and Moscow, the more secure Poland can feel.

The conference went on to elucidate however that a common enemy is not enough to unite people. With regards to Ukraine and Poland there is a lot of talk of forgiveness and brotherhood. In western Europe after the Second World War similar sentiments could be found being thrown about. The future of the Polish-Ukrainian relationship is dependent however on the ability of the two countries to take a leaf out of Jean Monnet’s book and work towards creating and pursuing mutual interests, and normality. It is with this in mind that one speaker at the conference made the point that unlike France and Germany, Poland and Ukraine are travelling in ‘different cars’. Poland is in the EU and NATO with a thriving economy while Ukraine is not yet meshed in security-blanket alliances and has a comparatively weak economy. As Europeans, and European Federalists, we must do our bit to bring Ukraine into our ‘car’ and proactively support it in fulfilled the criteria to become a member of the European Union. In doing so we will help spread peace into Eastern Europe and tackle one of the few large crises currently afflicting our continent.

A final few takeaway points:

Michał Boni MEP was supposed to attend the conference but was unable to and so sent along a speech to be read out to those of us in attendance. In it, he gave some concrete proposals on how to improve Ukraine and bring it into the same ‘car’ as the rest of us. One such suggestion was a quick move towards creating a federal Ukraine. This suggestion immediately got my attention as is always the case whenever someone uses the word ‘subsidiarity.’

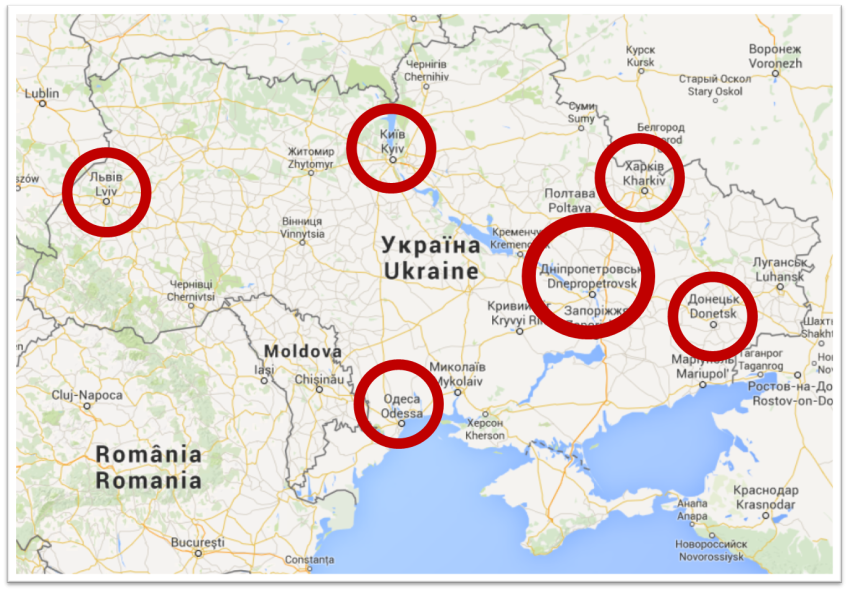

It was further supported by a discussion on the new Ukraine that is coming out of the current conflict. The centre of power in independent Ukraine has been an Lviv-Kiev axis – the capital and the country’s most ‘western’ city. Yaroslav Hrytsak however spoke about the new need to take into account Dnipropetrovsk (situated on the river Dnieper in the eastern half of the country. But an axis of three cities is still too small to do Europe’s second largest country (after Russia) any justice. We must also consider what the northeastern city of Kharkiv thinks about things; and of Donetsk in the south-east which is currently under occupation by Putin’s little green men. Then on the south-west coast of Ukraine is the city of Odessa which again takes a different attitude to things. Without even discussing occupied Crimea, it’s become clear that we have a multipolar Ukraine, which lends itself to federalism. Hopefully the Ukraine coming out of the Revolution of Dignity will treat all its provinces as such.

We came out of this conference optimistic about the present and future of Polish-Ukrainian relations; we even had some proposals on how to improve things further. But the final takeaway from this conference that hit home for a European Federalist concerned Russia. It’s all too easy in a room full of people sympathetic to the Ukrainian plight to fall into lazy stereotypes of Russia, and to ’other’ it as Europeans have ’othered’ one another so thoroughly in our modern history. We were encouraged to remember that the people of Russia do not equal its government. In a country where opponents get imprisoned or die in ‘mysterious circumstances’, we should all be heartened to see a Russia that continues to contain people who oppose aspects of the regime. It serves as a reminder that the European project is to create peace through union of the peoples of Europe. The Treaty of Rome did not exclude Russia from the process of European integration and so just as we held out our hand to Poles in the 1980s, and to Ukrainians now, we must also do our bit for the Russians. We must get everybody in the same car.

Follow the comments: |

|