To individualism, they oppose one of the most tightly knit religious communities of the present. To tolerance, they oppose the forceful integration described by the “good book”. To feminism, they oppose family. They counter the right-wing with state intervention and economic protectionism, but only for those of faith. They counter the left-wing with a religiously-imbued rhetoric that reeks of social exclusion. The center disgusts them, and for that reason they have secluded themselves into a self-sustaining bubble of religious morality, only peering out on occasion in order to spew judgmental critiques.

The First Steps

Cold morning in a small Transylvanian village not 15 minutes away from Timisoara, the beacon-city of the 1989 Revolution and one of the most prosperous and youthful cities of Romania. At her 82 years of age, Elena sits stoically on her front porch. She can no longer maintain her once-plentiful garden, relying solely on her state pension and the corner shop for her day-to-day food.

Looking around, she sees few familiar faces, and all of them marked by the passing of time. Young people don’t linger in the countryside anymore, most of them limiting their presence here for a few hours every month. Other elders, with relatives spread across Europe, aren’t so lucky. A few neighbors walk by, but only one nods his head her way respectfully. She mumbles a response. The community has not been the same since she joined the Baptist church a couple of villages away. People that she had known for decades now shy away from her.

However, Elena does not regret it. The welcoming people there provide her with much-needed human contact. The fact that they bury their members with church money is even more helpful, since all her former Orthodox priest used to do for her was to hold out his hand for more coin. At the new church, they often sing and praise the Savior with an enthusiasm that she had never seen before. At first, she thought it to be a bit strange, but she got used to it. Say the words, mumble a prayer, everything is much like her old church. And the face looking down at Elena from the cross is the same. That’s all that matters, she concludes.

But the ranks within which Elena has fallen are not the same as those which make up membership in your usual Orthodox Church. This evangelical church is politically involved, and its primary goal is to “save the children” from homosexual couples.

The Referendum

Ever since early in 2016, much ink has been spilled about defining something as bland as the family through the rigid lettering of the Romanian constitution. It was all started by a small band of loud-mouth anti-gay advocates united in the so-called Coalition for Family. The initiative for the referendum was kicked off by a show of force, with 3 million votes gather toward its organizing.

In Romania, 3 million votes can win you an election, or at least make sure that every political calculation has to include you and yours for years to come. As such, the major political parties, PNL and PSD, could not ignore the Coalition, which in turn fashioned itself into a kingmaker during the December 2016 parliamentary elections.

While PSD chose to support the pro-Coalition camp wholeheartedly, the liberals, as it pained them to be in agreement with their main rivals, tried out different stances, from open support for the referendum to its shy rejection, even attempting to ignore the matter altogether. The only party that seemed to struggle with its own stance on the issue was USR, the anti-system centrists which in the end remained deeply divided on the subject.

So where did they come from? While some point to financial backing from the east, it must be said that when we study their public behavior and messages,the Coalition is anything but original. Most of its talking points and marketing strategies come right from over the pond, from their evangelical brethren in the U.S.

Writer Vasile Ernu outlines the history of Protestant communities in the East. (1) He explains that these groups, which remained distant from Western Protestants for long periods of time, developed in a political, economic and social context that was extremely different from the one that birthed their Western counterparts. While English, German and French Protestants fought to throw the yoke of the Catholic Church, Eastern Protestants lived in harmony with the Russian Orthodox Church.

After 1989, Ernu identifies a virtual “colonization” process, with American preachers and televangelists coming to Eastern Europe with know-how and money. As a result, Romanian evangelists became allies of American ultra-conservatives that regard liberals and democrats as being no different from communists. And so Romanian evangelist churches ring of “worship songs” and so the Colaition employs the same strategies in its political activism as the Westboro Baptist Church.

For a Secular Europe

The term “Europe” itself is deemed to have been first used around the 9th century. Religiously-imbued, it was meant to designate the Western Church as opposed to the Eastern one, all in the context of the Carolingian Renaissance. The cultural space of the West, “limited to northern Iberia, the British Isles, France, Christianized western Germany, the Alpine regions and northern and central Italy”, all fell under the term “Europaoften” in the letters of Charlemagne’s court scholar, Alcuin. (2) It is time to sever the tie between Christianity and political institutions.

Pierre Manent, one of the conservative surveyors of religion in the European context, stresses that “the state could become neutral only after the French nation became, for most of its citizens, the “community by excellence”, surpassing the Church. For the secular state to become possible it was necessary for „France” to replace „Catholic France.”(3)

When the faithful had power and control over earthly institutions, they were merciless. Millions upon millions killed, mauled, burned on the cross, thrown into rivers chained to boulders, left to starve and every imaginable method of provoking suffering. All done and endured in the name of religion, of creed, of my human-god over your human or goat-god.

The Dark Ages are by no accident “dark”. They were the darkness of knowledge, the spawn of ignorance and hatred, the laboratory of torture and the work of self-justifying human cruelty. There have always been groups of fanatics that argued that humanity should revert back to that age of glory. Some adapted, changed their discourse, employed modern means and channeled their message. After all, it was religion that first used marketing, was it not?

Secularism, the right to not believe in the various gods put forward by the approximated 4,200 religions (4) that are at present crammed together in 195 states, is today taken for granted in Europe. This happens even though a jump back in the recent history of mankind would prove such a stance to be equivalent to suicide, even in the parts of the world that are today champions of progressive, non-religious thinking.

The Catholic Pope is at present progressive and takes a strong anti-mystical stance. Islam, despite the danger of terror attacks, does not pose an existential threat to the European political establishment. The political involvement of evangelicals in Eastern Europe, on the other hand, is a danger to European values of inclusion, tolerance, diversity, and consensual decision-making.

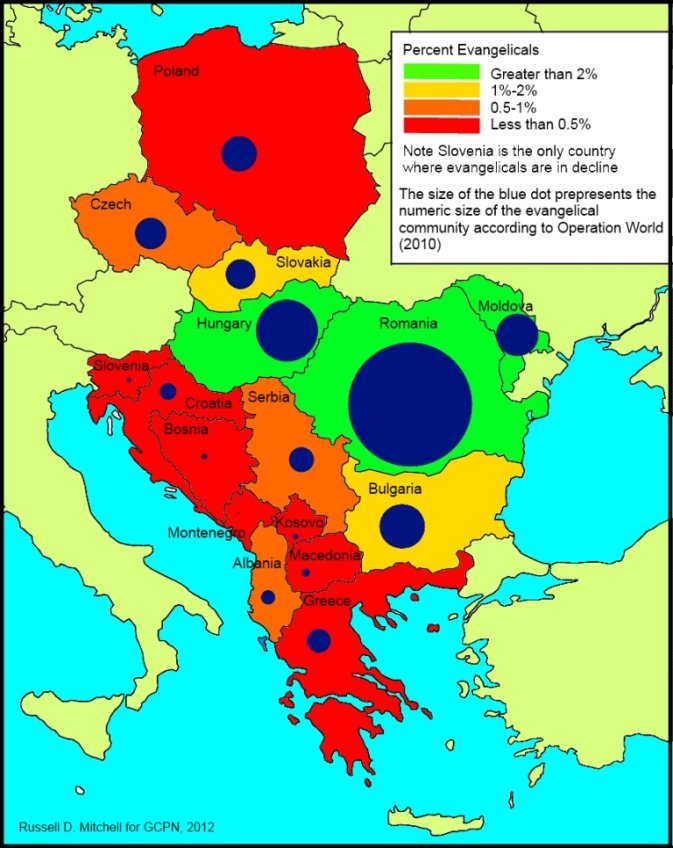

Often enough, religious obscurantism of the type and Euroscepticism go hand in hand, as the extremist evangelical communities are especially prone to seclusion and the adoption of an “us versus them” mindset. Protestants, which include evangelicals, represented 12.8% of EU’s population in 2010, according to a report made by the Pew Research Center. (5) By comparison, Muslims represent 5.8%.

Europe is not built on religion, despite the civilizational arguments that place Christianity at the core of European identity. We have long ago surpasses this tribal marker of collective identity. Why should we let a dying ghost come back to haunt us, influence our policies, stir hatred and racialism, justify violence once more and turn individuals against each other for an imagined god?

The motto of the EU, spelled out in 2000, is “united in diversity”. That principle applies not only at the level of the Union or of the states, but also to every individual. Religious extremism is the committed enemy of this core European value. As a result, the place of religion is strictly within the private sphere and not in political debates. Never again will we allow it to overtake our towns, cities, states, or our Union.

Sources:

(1) Vasile Ernu, despre ’pocăiţi’ şi Coaliţia pentru Familie: ’Cînd se va întoarce roata va fi dur’ at www.stiripesurse.ro (2) Norman F. Cantor, The Civilization of the Middle Ages, 1993, “Culture and Society in the First Europe”, pp. 185 (3) Pierre Manent, Les Raison des Nations. Reflections sur la Democratie en Europe. Editions Galliamard, 2006 (4) “World Religions Religion Statistics Geography Church Statistics” (5) Pew-Templeton Global Religious Futures Project

Follow the comments: |

|