The mandate of Maia Sandu as Moldovan president hasn’t been a smooth sail for pro-Europeans in the country and in the EU. The optimism regarding EU-integration raised by her victory in the 2020 presidential elections and her party’s (PAS) victory in the 2021 legislative elections was quickly swept away by the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 and the security threats it posed to Moldova. This EU-integration momentum had nevertheless been revived in the summer when the EU granted the country with candidacy status, before thousands of demonstrators coordinated and paid by pro-Russian oligarchs took on the streets of Chișinău calling for the resignation of the Maia Sandu and her pro-EU government. In this article we will try to look at the intertwining of these demonstrations with the pro-Russian narrative pushed forward by Moldovan oligarchs and the EU-integration stance taken by Sandu and her government in the context of the war in Ukraine.

From military menace to energy weaponization

In recent years, Moldova has taken a firm Western and European orientation which has dissatisfied Russia. Maia Sandu’s 2020 inauguration speech where she described herself as “the President of the country’s European integration (1) “ was one of its expressions, but more recently the war in Ukraine was an opportunity for Moldova to reaffirm this direction. Indeed, on 3 March 2022, following the Russian invasion of its neighbor, Moldova officially applied for EU membership before being granted candidate status later in June. These elements led Sergei Lavrov to say that Moldova (and Ukraine) would be “permanent […] minor players in the West’s games“ which will require them to show “full solidarity with the EU’s […] anti-Russian actions“.

This interpretation of Moldova’s westward orientation, later confirmed by Maia Sandu in an address before the Romanian parliament in November, paved the way to a number of military provocations by Russia. Throughout the first part of the war the Russian military leadership waged the threat of creating a corridor in Southern Ukraine which would connect Russia to the pro-Russian separatist entity of Transnistria where around 1500 Russian soldiers are illegally stationed (2), subsequently implying that the war could be expanded onto Moldovan territory. Moreover, the 10th of October, 3 Russian missiles targeting western Ukrainian cities flew over Moldovan territory further increasing the risks of an escalation. If no military operation was however triggered, Moldova nevertheless suffered from what government officials called energy and political “blackmail“ from Russia.

Moldova has been extensively dependent on Russia for its energy supplies since its independence. Indeed, 100% of its gas was imported from Russian energy giant Gazprom prior to the war in Ukraine. Part of these supplies were immediately redirected towards the Russia-backed separatist region of Transnistria, home of Moldova’s largest gas-fueled power plant in Cuciurgan which produces 70% of the country’s electricity which is then sold to Moldova. The separatist region of Moldova survives thanks to Russia’s support which exports gas to the region through Moldova, but never asks its authorities to pay for it. In this energetic scheme organized by Russia, Moldova pays twice for its energy supplies. Firstly, when buying gas from Russia, and secondly when buying the electricity produced (freely as we’ve seen) by Transnistria.

This quick description of Moldova’s energy dependency gives us an overview of the Russian noose which recently tightened around the country. In the early days of October, Gazprom announced it was reducing its supply of natural gas to Moldova by 30%. Following this decision, the Moldovan government was forced to reduce the quantity of gas supplied to Cuciurgan power station, while maintaining the pre-crisis proportions. One month later, on the 1st of November, the power plant briefly stopped exporting electricity to Moldova, further highlighting the country’s energy vulnerability. In addition to this, Moldova had been receiving electricity supplies from the EU through Ukrainian infrastructures (Moldovan and Romanian power grids are not connected), but the Russian bombing of these facilities deprived Moldova of another important source of electricity, leading to power shortages and to the tragic economic situation described by Maia Sandu in a recent interview to RTS. Gas is indeed 7 times more expensive than it was last year in Moldova, while electricity is 4 times more expensive, and inflation rose to 35% in 2022. This burdensome economic situation will quickly be instrumentalized by some political actors as we will see in a later part.

Moldovan oligarchy and EU accession

The internal political situation of Moldova is also worth exploring to understand the recent demonstrations and the role of oligarchs in the country. After having built an economic empire during the 2010s, Vlad Plahotniuc, one of the most important Moldovan oligarchs will get into politics and slowly get his hand over various political and judicial institutions as well as broadcasting channels. By 2015 the oligarch had almost total control over Moldova and did not hesitate to monitor and imprison his opponents both from the civil society and the political world. Two financial scandals will reveal the scope of his power and lead to his exile in 2019, the “Russian laundromat“case and the “‘theft of the century’’ where 8% of the country’s GDP (1 billion $) vanished from national banks in 2014.

Ilan Shor, the oligarch behind the recent demonstrations in Chișinău, was also involved in this last scandal as head of one of the concerned banks. Shor’s figure is interesting to analyze for his growing influence in Moldova’s public sphere follows the same pattern as Plahotniuc’s. Shortly after the scandal he entered politics by becoming mayor of Orhei thereby benefiting from an immunity from prosecution. Despite having had to flee the country in 2019, Ilan Shor continued to consolidate his influence from abroad by buying several TV channels which on top of broadcasting pro-Russian programs served as steppingstone for the organization of the demonstrations by diffusing his anti-government rhetoric to the public.

This rapid description shows the oligarchic gangrene which has been undermining the country for years with actors behaving, as researcher Vladimir Socor notes, as “Russian interests’ watchdogs “, a political posture which is at the antipode of Maia Sandu’s PAS party pro-European and anti-corruption agenda. Following the country’s accession to the EU candidate status in June, the Commission set out a number of areas in which reforms were to be made in order for Moldova to move to the next steps of EU accession process. These included justice reform, fight against corruption, strengthening of public administration, fight against organized crime and “de-olicharcization" (4).

This last part, which is of our interest in this article, is supposed to take the form of a “Magnitsky Act” inspired by the Ukrainian law of the same name. Targeting Moldovans associated with acts of major corruption or who collaborated with foreign intelligence services against Moldova, this law should transpose into national law the content of international sanctions taken by states or international bodies against these individuals. It should also allow the national administration to freeze the assets held in Moldova by these individuals and to sanction their entourage. Furthermore, the Audiovisual Council of Moldova should be able to withdraw broadcasting licenses from channels linked to sanctioned individuals. An important point given that at least 8 TV channels in the country are said to be linked to oligarchs Plahotniuc and Shor (5).

No wonder in these condition that the oligarchs targeted by these measures are up in arms against this “de-oligarchization“ process which embodies both the end of an era of unlimited power for oligarchs and of Russian influence in Moldovan politics, and confirms the pro-European orientation they execrate, taken by Maia Sandu’s Moldova.

Expensive cost of living, loss of political power: the instrumentalization of struggles

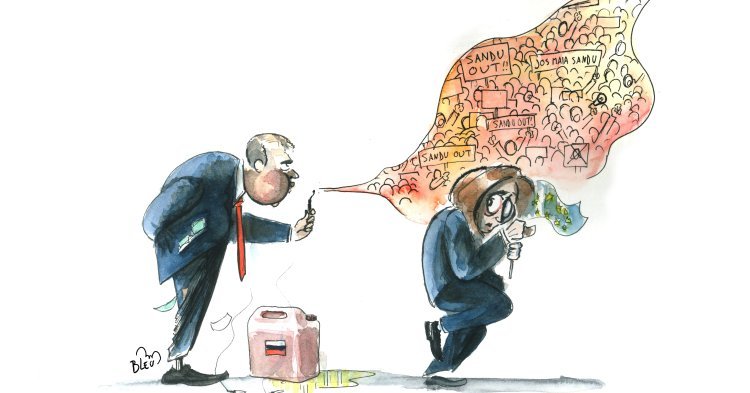

It is in the aforementioned context of burdensome economic situations for citizens and of slow oligarchic power loss that demonstrations took place in Chișinău last autumn in what could be described as an instrumentalization of the people’s economic struggles by some oligarchs against the government. In 19 September 2022, the first demonstration was organized at the initiative of the ȘOR party leaders with the help of their media communication channels, gathering around 20 000 people (6) in the streets of the Moldovan capital city. Regular demonstrations took place in the following weeks and by the end of the month of September, tents were pitched in front of the residence of the Presidency. Behind the slogan “Jos Maia Sandu“ (“Down with Maia Sandu“ in Romanian), the demonstrators called for the resignation of both the President and the Prime minister, holding them accountable for the difficult economic situation in the country.

If the right to demonstrate is one which is protected by article 40 of the Moldovan Constitution, problems with this specific mobilization soon arose. Indeed, an investigation published on the 3rd of October, the online media ZdG.md revealed a system of transportation and remuneration of demonstrators set up by the ȘOR party to increase the number of people on the streets. Infiltrated journalists have shown the details of this operation where buses were chartered to bring people from around Moldova to Chișinău and where demonstrators, in exchange of 2 hours of “active demonstration“, were paid 400 lei in cash.

A couple of ȘOR activists were moreover arrested carrying a bag with 380 000 lei in cash probably used to remunerate the demonstrators (7). These unlawful practices coupled to the context of the war in Ukraine and the proximity of Ilan Shor with Russia, which has been exposed by an investigation from RISE.md, led Maia Sandu to qualify these demonstrations of “destabilization attempts” (8) and to call for the police to intervene to restore order (9).

If the demonstrations slowly lose momentum, they have shown the capacity of oligarchs to instrumentalize the struggles of the Moldovan population. As we have tried to show in this article, the energetic dependency situation in which Moldova finds itself has been a lever used by Moscow to blackmail Chișinău for the firm EU orientation it took and for its support to Ukraine. This has led to a difficult economic situation in the country which has been instrumentalized by oligarchs who orchestrated and illegally financed a public mobilization calling for the resignation of a government whose EU-orientation had been detrimental to the oligarchs’ political and economic stronghold over Moldova.

In this context, it is crucial for the EU to continue supporting Moldova in alleviating the consequences of this pro-European orientation and to dodge the hurdles placed by Russia and their henchmen on Moldova’s EU integration pathway.

(1) https://www.presedinte.md/eng/discursuri/discursul-inaugural-al-presedintelui-republicii-moldova-maia-sandu (2) РОМАЛИЙСКАЯ, Ирина ““Ни одна страна, на чьей территории находятся российские войска, не может решить этот вопрос”. Выйдет ли российская армия из Приднестровья“, Настоящее Время,30 ноября 2020 (3) SOCOR, Vladimir. “Moldova’s Bizarre Neutrality : No Obstacle to Western Security Assistance (Part. II), Eurasia Daily Monitor, Vol. 19, Issue 124, Jamestown Foundation, 15th August 2022 (4) https://mfa.gov.md/ro/content/vicepremierul-nicu-popescu-prin-aprobarea-planului-de-implementare-celor-9-recomandari (5) “Actul Magnitsky” în interpretare moldoveană și televiziunile oligarhilor“, Radio Europa Liberă Moldova, 13th December 2022 (6) TANAS, Alexander. “Thousands take part in anti-governement protests in Moldova“, Reuters, Chișinău, 18th September 2022 (7) ZABRISKY, Zarina. “The spectre of the FSB haunts Moldova, next target of Russia’s hybrid war“, Euromaidan Press, 13th December 2022 (8) CǍLUGĂREANU, Vitalie. “Noua miză a Rusiei în Moldova – o grupare “pentru hoție și război” ce urzește destabilizarea“, Die Welt, 11th October 2022 (9) “Președinta cere ca poliția să poată interveni la proteste evitând autoritățile locale“, Radio Europa Liberă Moldova, 11th October 2022

Follow the comments: |

|