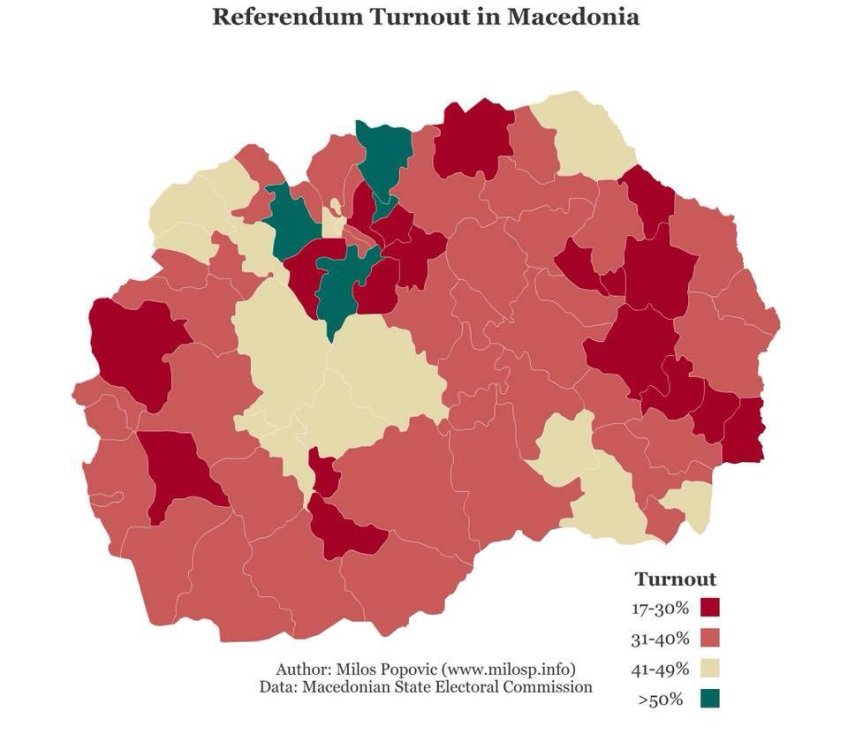

If you are crying after seeing the low turnout at Macedonia’s referendum on its name change with the prospect of Euro-Atlantic integration – stop. If you are cheering that over 600.000 people voted in favour of the deal, also stop. Here are a few reasons why.

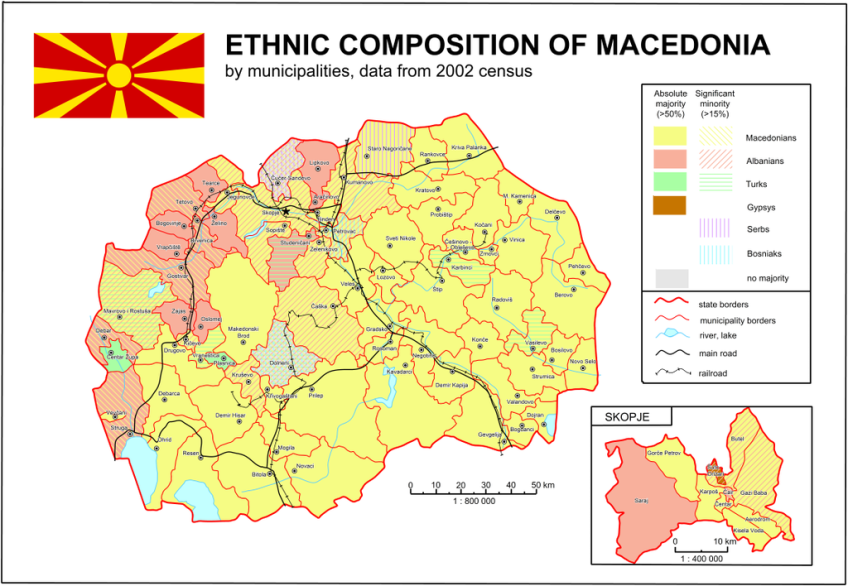

First, the very idea behind boycotting instead of circling one of the two given answers at the referendum, to the detriment of the national interest, is petty. Also, the wildly inaccurate voter register aided the boycotters, since the voter turnout required for the referendum to pass was set at no less than 900.000. For a country that has spent the last 16 years without updating its population census, counting 1.800.000 eligible voters is quite optimistic and contradicts the estimates that there are only around 1,500,000 voters. The expected support for the referendum by the majority of ethnic Albanians only partially corresponded with the ethnic map of the country, and there is no factor other than the voter register that could explain that.

The government spent a significant amount of time and money on organising the referendum without having met the obligations the EU had set for the country in 2015 while it was in a deep political crisis – clearing the voter register. This made it impossible to predict the potential turnout and gave room for the boycotters to celebrate a victory.

On the other (brighter) side, if the opposition party supported voting for the referendum and circling “No”, and if the turnout was the same as the turnout for the last Parliamentary elections (more than 66%, which, on the other hand, was higher than the usual turnout), then the referendum would have ended in favor for those rooting for EU and NATO integration. Also, no other party or cause since Macedonia’s referendum on independence has gained more support than this Sunday’s referendum question, which is a strong reason to cheer. On the other hand, such a vast number of boycotters undermine the very optimistic projections stating that around 75% of the population support EU membership, which were supposed to be boosted by the numerous visits by high-profile EU and NATO officials and heads of state of EU members.

One of the main boycott narratives was to equate support for the referendum with SDSM party support, and the people who showed up and voted were framed as traitors. The SDSM leadership now also seems to be making the same mistake – equating the support for the deal to support for the party. This gives them the confidence to schedule early elections, but the lack of credible sources on party support might mean that the country sees similar results as in 2016, meaning another stalemate at the expense of progress. According to some sources, SDSM’s rating is still ahead of VMRO-DPMNE’s, but difference between the two parties, less than 5%, does not encourage such confidence.

Overall, the taxpayers paid for the unsuccessful referendum and the campaign, and they are going to pay for the potential early elections, whereas the absurd name issue is still blocking Macedonia on its path towards the EU. If the negotiation is prolonged again, Macedonia will undoubtedly come across a much less lenient Greek position. The latest 2019 election polls predict dire future for Alexis Tsipras’ Syriza and a probable landslide victory for Nea Democratia – one of the parties arguing most vociferously that the deal was too advantageous for Macedonia. The clock is ticking for Macedonia. It is high time to stop pressing the snooze button on such an absurd issue.

Follow the comments: |

|