In The World of Yesterday, written shortly before his suicide, Zweig painted a picture of a Europe long gone: one of Parisian cafés, of Austrian literary circles, and of summers in the Belgian seaside town of Ostend; one which died “on June 29, 1914, in Saravejo”, where “the shot was fired which in a single second shattered the world of security and creative reason in which we had been educated, grew up and been at home”.

Upon Zweig’s return to Ostend in 1936, notes Marc Bassets for El País, the atmosphere had changed beyond recognition. And at the time of writing, in 1942, the tables had turned dramatically: the wave of nationalism and fanaticism which infected the continent, writes Amos Oz in A Tale of Love and Darkness, targeted the very idea of a united Europe, free of borders and bound by a common culture, which Jews such as Zweig himself had pioneered.

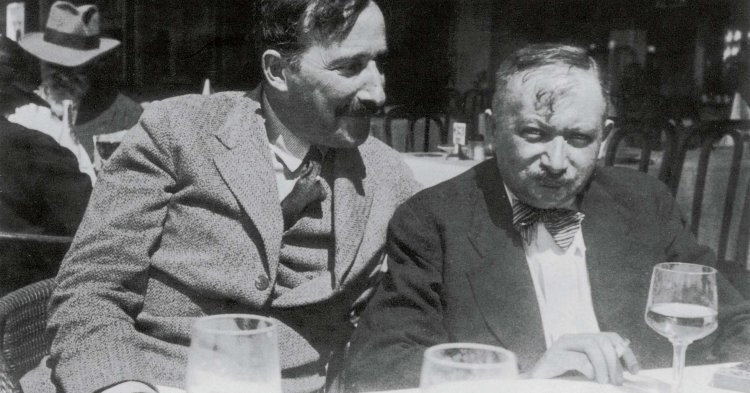

Looking back on his days in Ostend, Zweig’s tone is nostalgic, but also expresses perplexity at how such a state of affairs was taken for granted: by national politicians, who assumed that diplomatic conflicts “were always happily settled at the last minute, before things got too serious”; by the intellectual elite, which viewed war either as a distant threat or as a necessary evil which would soon pass; and by the “happy vacationists” in Ostend, whose only disturbance was “the newsboy, who, to stimulate business, shouted the threatening captions in the Parisian papers”. In hindsight, he wonders, could such an outcome have been avoided - could an open, interconnected Europe have been saved?

As early as the the 19th century, transnational travel was central to the idea of a common European identity. Integration was not a top-down project, but an increasingly frequent day-to-day reality, shaped by waves of rank-and-file Europeans who moved, almost in a Tolstoian fashion, from one end of the continent to the other: from their German homes to the Belgian beaches; and from Austrian concert halls to their Italian summer residences. In The Europeans, in fact, British historian Orlando Figes traces the idea of a unified Europe not to political manifestos or geopolitical strategies, but to the birth, in 1834, of the first transnational railway line – from Cologne to Antwerp –, which democratised a life which had formerly belonged exclusively to the continental bourgeoisie. It is against this backdrop, nearly two centuries later, that the Covid pandemic has struck.

A summer without travel, writes Paola Tamma for Politico, is particularly startling for the so-called ‘easyJet generation’, born and raised in a Europe of weekend escapades, of cheap flights, and of a Eurostar which Simon Kuper deems worthy of a ‘Zweigian fantasy’. Through Schengen, generations of Europeans have crossed the continent without the need for passports or border controls; thanks to Erasmus, they have lived, loved and raised families across Europe. This author’s own European identity, in fact, owes more to bus journeys to Luxembourg, night trains to Florence, and weekend trips to Sofia, than it does to party political projects or inter-institutional agreements.

When the pandemic hit Europe back in March, there remained hopes that it would be a one-off setback. Following a necessary lockdown, one naïvely dreamt, the virus would fade away. Come the summer, life as usual would return: bags would be packed, tickets would be booked, and travel would resume. Yet 106 years after Zweig’s trip to Ostend, Europe’s summer has similarly been brought to a halt. This is a year without road trips or trains; one of quarantines and passports. It is a year which showcases the extent to which we have taken travel for granted – but also, perhaps, the extent towards which it has shaped who we are as Europeans.

Sooner or later, the virus will pass. And although it will not have killed the European project, as some commentators feared and many a far-right politician hoped – it may, indeed, strengthen it –, it will have showcased Europe’s fragility. As Ostend’s “happy vacationists” learnt, Kuper concludes, there is nothing inevitable about Europe’s borders remaining open, or re-opening once they have been shut: if Zweig’s memoir can teach us anything, in fact, it is that the European project takes decades to build, but can be destroyed in a single day.

In the midst of fierce political debates surrounding European integration, with two Member States straying increasingly far from democracy, and with populist governments using the pandemic to close their borders, dismantle their democracy and feed xenophobic nationalism, The World of Yesterday serves as an invaluable reminder of the centrality of open borders: integration may be imposed politically, but a true European identity – the demos which Amos Oz’s ancestors once dreamt of belonging to – can only be forged through travel. May the summer of 2020, the summer travel ceased, serve as a warning. May we never take open borders for granted.

Follow the comments: |

|