Only a few weeks before the COP 21, European internal difficulties have claimed another victim: the environment.

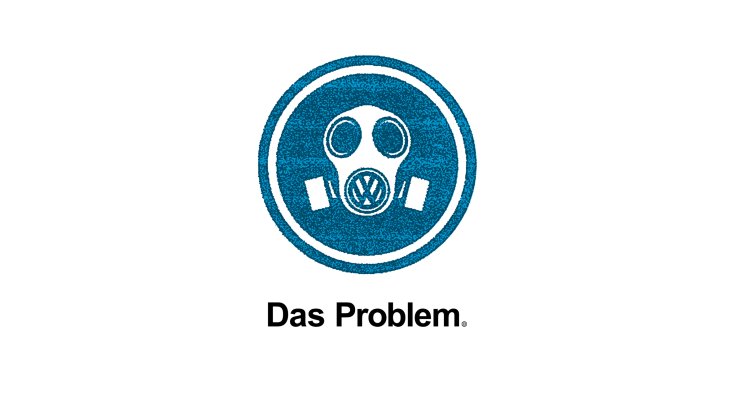

In September 2015 one of the biggest scandals in the automobile industry in history was revealed worldwide. The German car giant Volkswagen admitted cheating emissions tests in the US, thus evading clean air regulations. About 11 million cars will have been affected, and most of them are in circulation in the European Union.

One month after, in October 2015, the European Parliament refuses to open an inquiry into the Volkswagen emissions scandal. Several European Parliament committees, led by the Greens, recently proposed opening a parliamentary committee of inquiry in order to investigate how the car giant could have cheated the system and determine the role played by the Commission and other member states. The proposal was rejected by 453 votes.

This unexpected decision of no opening of any inquiry into the Volkswagen scandal raises attention and is very surprising. Empirical evidence and scientific data have indeed been collected by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and it clearly shows that many Volkswagen cars sold in America have a “defeat device” in diesel engines to escape clean air standards. The violation is thus scientifically and judicially stated.

So why then is the EP so reluctant to open any kind of inquiry into the scandal?

Political and economic reasons

Many would argue that the EP has a complex and long relationship with groups lobbying for diesel fuel. The Financial Times has recently revealed that Janez Potocnik, former EU Commissioner for Environment, was informed about the scandal in 2013, as well as Antonia Tajani, former EU Commissioner for Industrial Policy.

The weaknesses of a young and unstable European legislation

The Greens also admitted the current flaws of EU legislation on environmental issues. According to the current legal rule establishing the pollution threshold, adopted in 2007, test-emissions are realised in the laboratory - and not under real-world - conditions.

In this view, the European Commission has recently called for those tests to be replaced by tests under real driving conditions. However, this proposition includes numerous exemptions: car makers would be allowed to sell cars exceeding the legal thresholds of 50 and 60%.

The refusal to open any parliamentary inquiry means that the member states have to conduct their own national investigations. A number of inquiries have opened in France for example.

A few weeks before COP 21, it appears that Europe is not sufficiently prepared to address climate change. Although initiated efforts should be welcomed, European regulation on environmental issues remains young, little adapted to the realities on the ground, and subject to political and economic uncertainties.

One element, however, is clear: the environment is more than ever a matter of crystallisation whose treatment will have great impact on the legal and political organisation of Europe.

Follow the comments: |

|