On the morning of May 8th millions of Britons woke up, turned their kettle and radio on, looked out the window and sighed. Some expressed relief, others disappointment, but for a growing number of pro-Europeans, it was a deep sigh of unhappiness as the radio announced the triumph of David Cameron’s Conservative Party in securing a majority government, a record 3.9m votes for UKIP, a crushing defeat for the Liberal Democrats and a shock disaster for the Labour Party. The country was not seized by a great wave of euphoria for change like in 1979 or 1997, stable continuity was the order of the day.

The 2015 General Election marks the beginning of the most important five years in Britain’s relationship with the European Union. The implications of its result are three-fold: an in/out referendum on Britain’s membership is now a certainty, a combative conservative government will head to Brussels with a mandate for EU reform, and a continued lack of leadership in foreign and defence policy will characterise Cameron’s premiership as Britain’s government looks inwards to digest Scottish nationalism and its counter reactions in England and Wales.

As Francesco Violi mentions in his article, David Cameron faces the most monumental challenge of any statesman: keeping his country united. Britain’s existence as the kingdom we know depends on it.

The Referendum

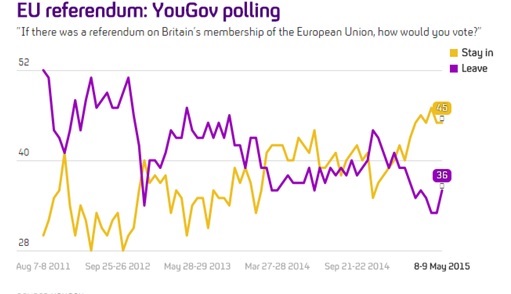

If Britain were to have a referendum today, we would vote to stay in. YouGov’s poll, taken the day after the election, showed a record high of 45% would vote to stay in compared to 36% against. [1] While the prevailing sentiment in 2012 and 2013 was to leave the EU, the trend is negative and has been slowly diminishing as Europe gets more coverage and the case for staying in is fleshed out. [2]

The case for Britain’s membership is strong and its backers are numerous, including every political party except UKIP, the universities, the arts, unions, agriculture, both big and small business as represented by their industry bodies, the Confederation of British Industry and Federation of Small Business, and the near totality of UK media. Leaving the Daily Express tabloid, a handful of hedge funds in the City, UKIP and its eccentric multi-millionaire donors. This is cause to be confident but not complacent. The combined forces of Rupert Murdoch’s anti-European grip on British politics and a potential euro-crisis sparked by a real or perceived Greek exit could tilt public opinion back again.

A combative government intent on reform

Two days after the election result, a beaming David Cameron announced that “the first thing is to get the renegotiation going and we’ll be doing that very soon. I’ve already made calls to European leaders”. [3] For the first time in 18 years, Britain has elected a full Tory government, and, unbridled by pesky coalition partners, the Conservatives are suiting up for Brussels to demand change. Importantly, Cameron will not demand a Treaty change since he has wisely realised he is not in a position to challenge the EU’s core freedoms. Instead he will try to bend the EU’s accommodating relationship further to his advantage. The UK government will lobby for a protocol not to commit the country to ever closer union, protections for the City outside the Eurozone, tougher migration regulation based on a two-year wait to become eligible for benefits, a commitment to further liberalise EU markets and greater accountability of EU institutions. Aside from EU reform, the Conservatives pledged to repeal the Human Rights Act and exit the European Convention on Human Rights to replace it with a UK Bill of Rights. Their motivation is not national interest but the need to have kept the Tory party united during the election and assuage right-wing appetite for European blood in its aftermath. The arguments advanced by sceptics against the ECHR are wrong. The court is an international not a “foreign” court and a British judge sits on all British cases. As Lord Bingham challenged, which internationally agreed human right would Britain actually want to drop? None. [4] Thankfully, the feasibility of this reform is unlikely, since the House of Lords will block any withdrawal from the ECHR. [5]

Little Britain, Tempestuous Kingdom

Faced with trouble and strife at home, Britain will turn inward over the next few years as the government works to keep the nation united. As a result, Europe’s biggest defence spender and nuclear power will take a back-seat, leaving France and Germany to take the lead in European diplomacy, and result in further undermining the EU’s ability to act on the global stage at a time when it faces conflict on all its borders. [6] Instead of global politics, Cameron will tend to little Britain as he nurtures a fragile economic recovery, treading carefully between political deadlock in Scotland and playing safe in England in order to hold onto his 12 seat majority. In addition to the challenges of identity politics, the next round of public spending cuts will also act as an obstacle behind greater external action. The £32bn of cuts will carve another deep slice out of most government departments including a reduction in defence spending below NATO’s required 2% of GDP. [7]

There is hope yet

Britain’s relationship with Europe is undergoing a mutation, thankfully it is a positive one. Constant euro-crisis coverage pulled the European Union out of the back pages of the business section and onto centre stage in the debate about who we are and where we want to go as a country. And as we speak, the massive wheels of British power, money and media heft are slowly grinding into action to eventually launch a cross-party campaign to save Britain’s EU membership. Something resembling the campaign against Scottish independence, Better Together. The current odds point towards its success, but nothing can be sure in a country where heartfelt arguments in favour of the Union have not been made consistently for 30 years.

Follow the comments: |

|